Why did Socrates insist on going through with it? Why did he administer the lethal dose of poison himself?

He did so because the law required it, and it is a citizen’s duty to obey the law. He said to friends trying to stop him—trying to “talk some sense into him”—that the laws had provided for his parents’ marriage, making him a legal citizen of Athens at birth. He pointed out also that the laws had provided for his education. For these reasons the laws were as good as his parents and teachers. What’s more, he said, he was in an implied contract with the laws. The laws never prevented him from leaving Athens, and taking all his goods. So by choosing to live there his whole life he had implicitly agreed that he would obey the laws. His breaking the law would therefore be three times wrong: he would disobey his parents, and disobey his teachers, and he would break a promise.

Did all this really happen?

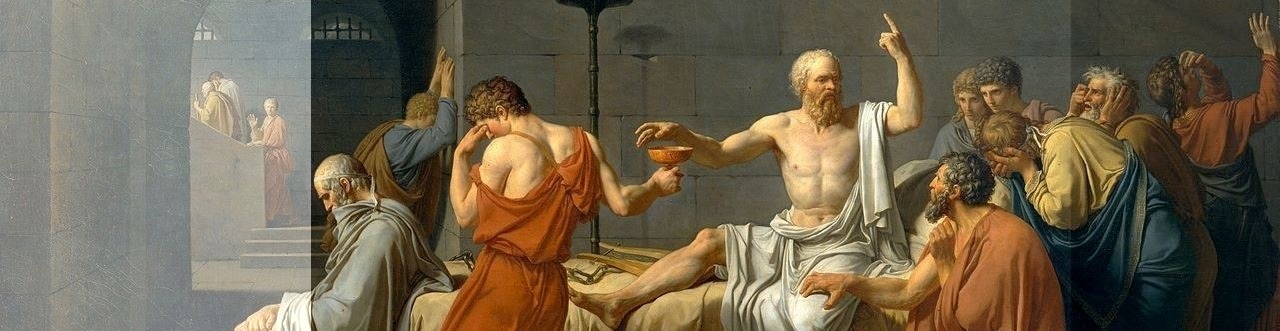

It doesn’t matter. We have the story of the death of Socrates from Plato’s writings. Plato, who is seated on the left in David’s painting, was Socrates’s student. The point the story raises, whether it’s true or not, is a hard question: Why should anyone ever obey the law if he can get away with breaking it? It’s similar to another question that Plato asked: Suppose you could live unjustly, even criminally, and be certain that you would never be found out. Under those circumstances, why not live that way? Why be moral?

I sometimes think about that question while driving

on the

highway, when no state police are around.